5 Ideas to Carry Into 2025

Musings on Handwriting, Metamodernism, Longform, Down-Versus-Up, and the Definition of "Content."

Happy New Year! Even if you’re as curmudgeonly as Larry David, I still think we’ve got a few more days where saying “HNY!” is socially acceptable. Whether or not that statute of limitations has expired, I’m offering this: my post to set the tone for 2025.

This year, instead of bold resolutions, I’m grouping a few ideas that have been rattling around my brain. These aren’t goals so much as principles I want to carry with me, and I’ll share them here in case they spark something for you:

1. Handwriting

Toward the end of 2024, I noticed a flood of posts extolling the benefits of handwriting. One study especially stood out: “Handwriting but not typewriting leads to widespread brain connectivity.” The authors explained that handwriting activates more elaborate brain connectivity patterns than typing does—particularly in regions tied to memory formation and learning. Their conclusion was compelling:

“We urge that children, from an early age, must be exposed to handwriting activities in school to establish the neuronal connectivity patterns that provide the brain with optimal conditions for learning.”

Handwriting requires complex motor movements, while typing involves far simpler, repetitive actions. It makes sense that the former would have a stronger impact on our brains.

Yet, as a society, we’ve largely replaced handwriting with digital devices. Well-meaning school administrators likely believed that teaching typing skills would better prepare students for a tech-based workforce. What they didn’t anticipate was that handwriting wasn’t just a nostalgic pastime—it’s a far more effective tool for learning and encoding information.

I think back to my favorite math teachers who worked out problems step by step on the chalkboard. Watching them physically write out their process helped to make the concepts click.

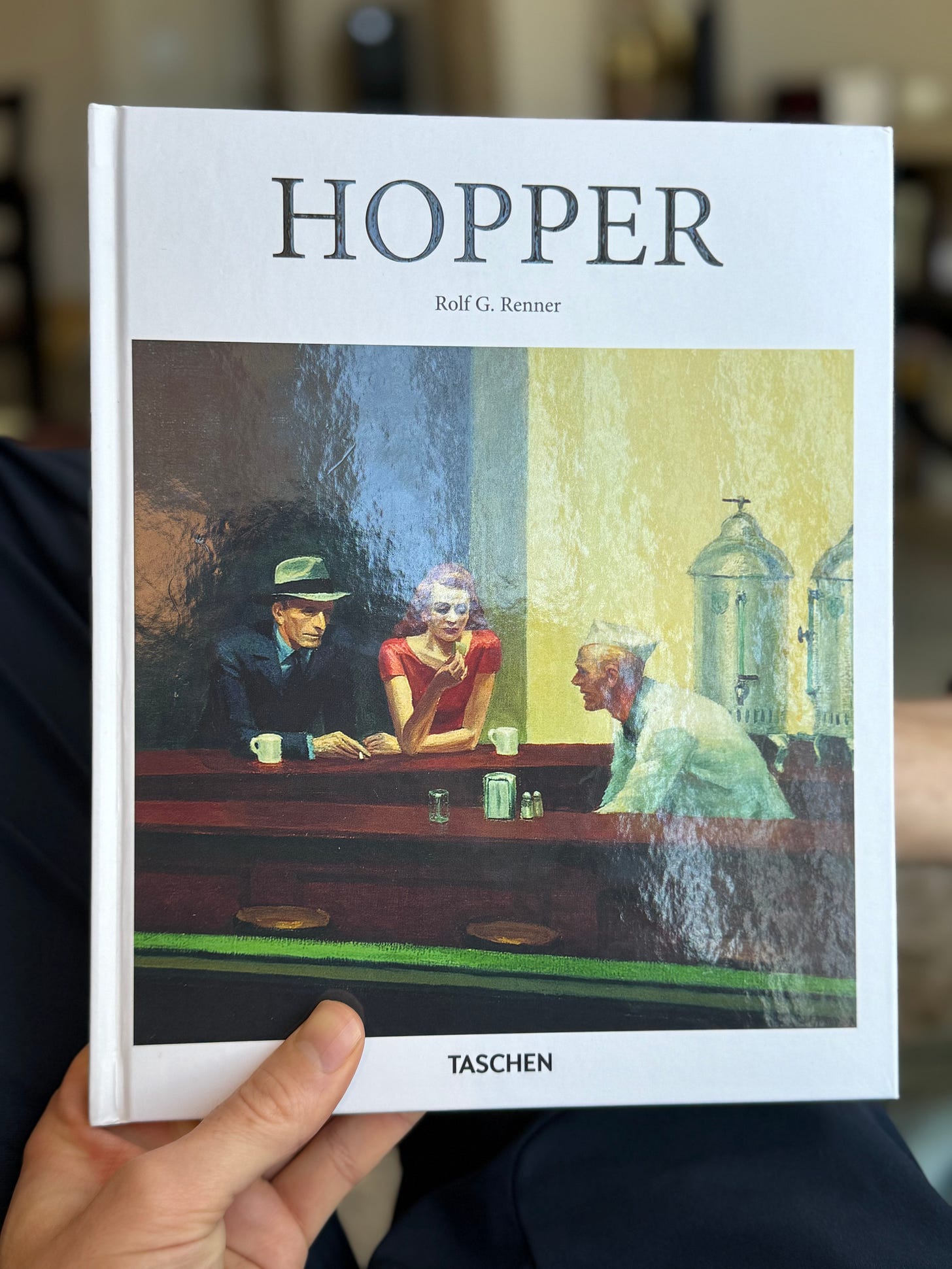

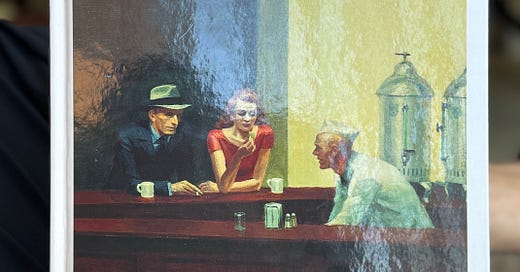

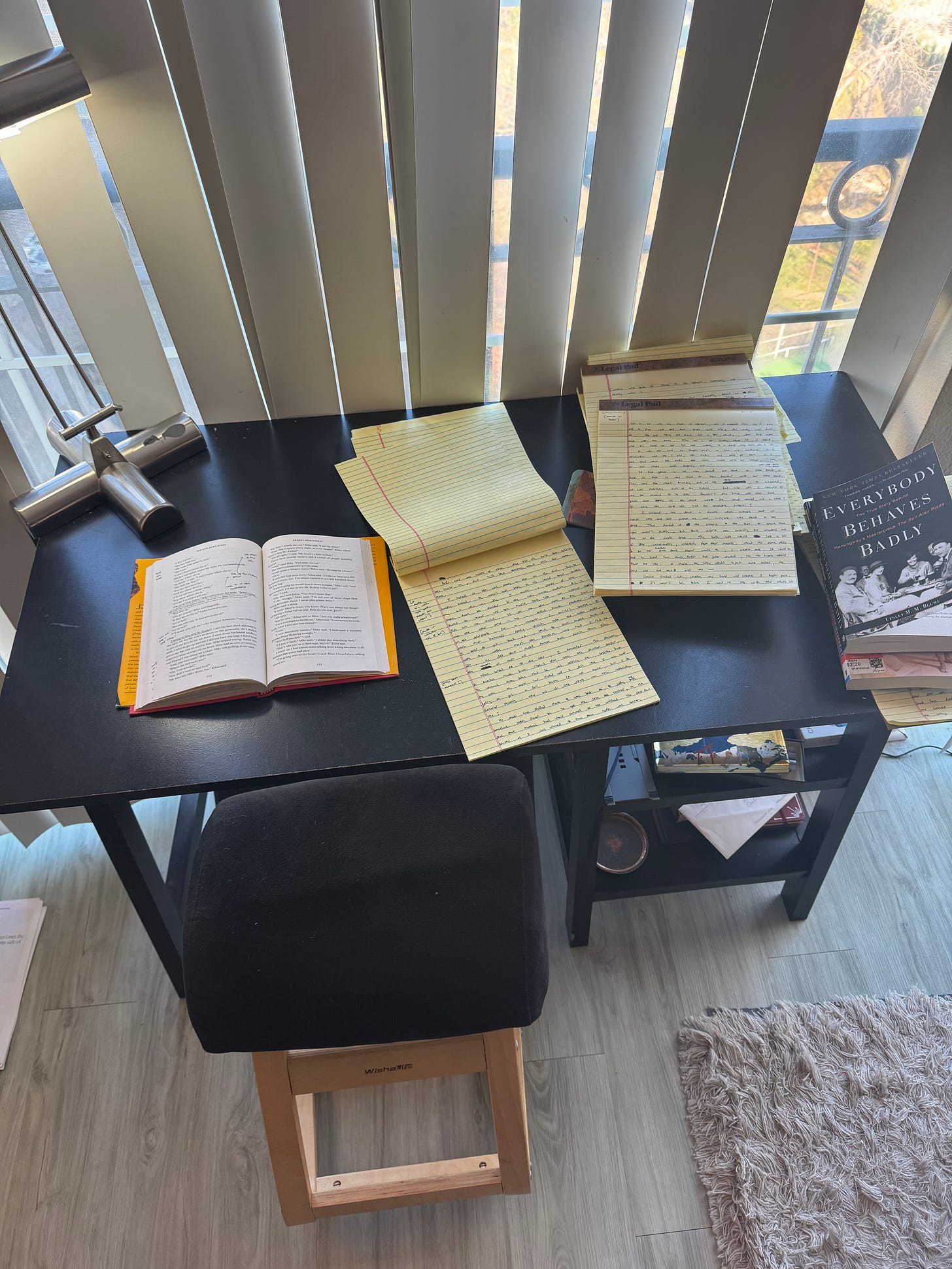

Inspired by this research—and a desire to try things differently this time—I’m writing the first draft of my next novel by hand. Writing out the chapters on yellow legal pads is a much slower process than typing, but it feels easier to pick up the story where I left off each day. Perhaps the act of handwriting does indeed build more connections across the brain.

2. Metamodernism

Wikipedia defines metamodernism as:

“a cultural discourse and paradigm that has emerged after postmodernism. It refers to new forms of contemporary art and theory that respond to modernism and postmodernism and integrate aspects of both together. Metamodernism reflects an oscillation between, or synthesis of, different ‘cultural logics’ such as modern idealism and postmodern skepticism, modern sincerity and postmodern irony, and other seemingly opposed concepts.”

If you’re curious about metamodernism, you might find a well-made YouTube explainer, like this overview from Living Philosophy, to be the best starting point.

That said, let me break it down with a superhero analogy:

Modern idealism is like the original Captain America (1941): a clear-cut symbol of nationalism and duty, fighting for freedom and democracy with moral clarity.

Postmodernism, by contrast, deconstructs these ideals. Think Watchmen (1986), where the heroes are deeply flawed, truth is murky, and defining the “good guy” depends on your perspective. Or Deadpool, with its self-aware humor, irony, and cynical take on heroism.

Now, enter metamodernism: a “vibe shift” that moves beyond modern idealism and postmodern skepticism. Instead of choosing one mode, it oscillates between the two. Some say it pushes through postmodern irony to arrive at something more earnest. This “new sincerity” blends hope with self-awareness.

Take Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022), a film many critics consider metamodern. The narrative revels in absurdity but lands with a moment of heartfelt sincerity. Or look at the resurgence of the band Creed. Once dismissed as cringe (a classic postmodern insult), they’re now being reclaimed as post-cringe.

Even superheroes are evolving. On YouTube, Deep Talks pastor Paul Anleitner predicts the forthcoming Superman movie will introduce the first explicitly metamodern Superman. He won’t be defined by naïve idealism or ironic detachment. Instead, he’ll embody a hopeful yet self-aware sincerity—a hero for the modern age.

Look up in the sky! It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s metamodernism soaring into the zeitgeist!

3. Longform

I’ll admit that I often forget what I hear on podcasts—my attention tends to drift. But every now and then, something sticks. A while back, I heard Yuval Noah Harari, author of Sapiens, share advice that felt spontaneous yet profound. He was speaking about the value of longform content over shortform:

“Throughout the day, have an information diet […] Be very aware of what enters your mind.

So for instance, I read long books. I do many interviews. I prefer three hour interviews to five minute interviews. The long format, it’s not always feasible, but you can go much, much deeper. […] Give preference to big chunks. […] Books over Twitter, definitely.”

Longform—whether it’s a book, an in-depth article, or a sprawling podcast—offers depth, nuance, and the chance to engage with ideas on a more meaningful level. In contrast, shortform content, like TikTok videos, provides a quick dopamine hit but rarely leaves you any wiser. I’ve fallen into the scrolling trap more times than I’d like to admit, only to realize how little value I’ve gotten from that time.

As 2025 unfolds, I suspect the pull of shortform will only grow stronger. Better to stick with more “nutritious” options: books, thoughtful essays, and longform podcast discussions—literature or content (more on that word later) that’s more likely to be transformative.

4. Down-versus-up

’s Substack, The Honest Broker, has become one of my go-to reads. Last year, he wrote about what he sees as an emerging dimension of cultural conflict. “Analysis of cultural conflict is still obsessed with left-versus-right strategizing, but the actual battle lines are increasingly down-versus-up.”

The targets in this conflict are the elites—those perceived as sitting at the top of the social hierarchy. Gioia lists wealthy CEOs, DC politicians, celebrity TV newscasters, law enforcement authorities, experts of all stripes, Ivy League academics, movie stars, and other figures of authority or expertise. “All of the cultural energy right now is on the bottom. And that energy has been intensifying,” he observed.

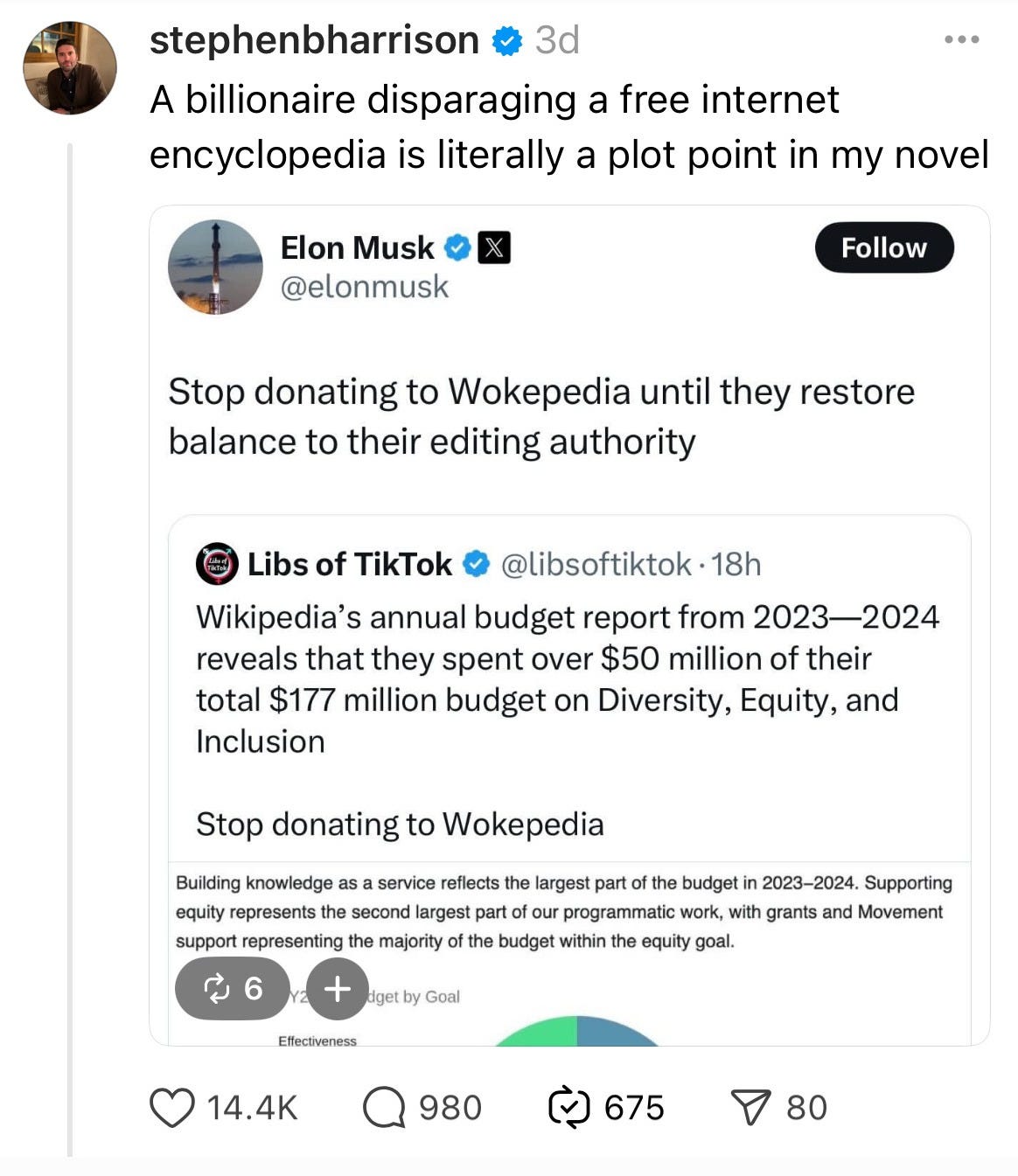

After publishing The Editors last year—a novel centered on a crowdsourced internet encyclopedia—I’ve been paying attention to how this “down-versus-up” dynamic is playing out in discussions about Wikipedia. A recent example came on Christmas Eve, when Elon Musk attacked Wikipedia, accusing it of being controlled by a woke “editing authority.”

From one angle, you could interpret Wikipedia as an elite institution—it’s the official, authoritative internet encyclopedia. But isn’t this a bizarre twist in the “down-versus-up” narrative? Musk, the world’s wealthiest man, is positioning himself as a populist punching up at Wikipedia. Meanwhile, Wikipedia itself is, in many ways, deeply egalitarian: anyone can edit it, regardless of their academic or professional credentials. (Granted, there’s no guarantee your edits will stick.)

What does this down-versus-up dynamic mean for Wikipedia—or for other battlefronts—in 2025? I don’t have the answers yet, but I suspect we’ll see more strange and paradoxical manifestations of this tension in the year ahead.

5. Definition of content

I’ve always been reluctant to call writing “content” because I worry that the term cheapens the craft. As Jon Christian put it in Slate back in 2016:

“I find the find the idea of someone aspiring to create content, in as many words, to be almost indescribably sad. It seems like an act of pre-emptive surrender, of giving up hope that you’ll ever create something with a higher calling than attracting clicks for some monolithic publisher.”

And yet, here we are—living in the age of content. Platforms thrive on user-generated content, politicians use content to dominate conversations, and authors are encouraged to release content to build their audiences.

But what exactly is content? And how does it differ from art?

On this point, I found an illustration from

’s particularly insightful. Stein highlighted the New York Times’s article, “100 Best Books of the 21st Century,” as a prime example of content. (When the list was published, I noted how it was surprising that so few of these books engaged with the internet, despite focusing on books published since 2001).As Stein correctly observed, the Times’s list wasn’t journalism or literary criticism. It was content—a post designed to encourage reader participation and spark more user-generated content, like the torrent of passionate videos covering the books the Times had snubbed.

The books themselves? That’s literature. The list? That’s content.

This distinction has helped me rethink content not as a diminished form of writing but as a participatory game—an invitation for audiences to engage, react, and toss their own content back into the mix.

One More Thing

I’m launching a monthly virtual book club for 2025! Who says the literary man is going extinct?

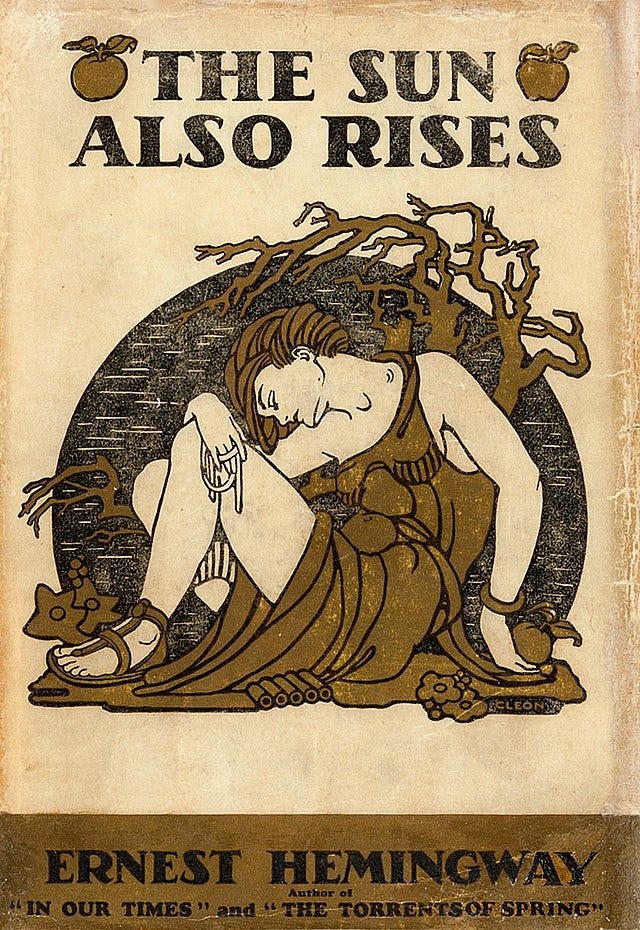

For January, we’ll kick things off with Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. The novel takes us through the literary circles of Paris, the bullfights of Pamplona, and the decadence of the so-called Lost Generation after World War I. Although the book is nearing its 100th birthday, I have a feeling its themes will resonate. Lost Generation vibes are strong these days.

If you’d like to join, drop me a comment or an email! For now, we’ll keep the book discussion here on Substack, but I’m open to organizing a live session if there’s interest. Bonus points if you also pick up Everybody Behaves Badly, an account of the real-life events that inspired Hemingway’s breakout novel.

HNY (again),

Stephen

Another thing: I’ve also hated the term content, feeling that it’s a cheapening of writing, but the way you’ve reframed it is fairly useful. I don’t hate content when you put it this way.

Really fun piece Steven, and I love the parallel to Musk and your book (which I finished over the holidays, very happily). I’m in for the Hemingway book club thing, however you do it.